Spring unlocks the flowers to paint the laughing soul.

— Bishop Reginald Heber

Spring unlocks the flowers to paint the laughing soul.

— Bishop Reginald Heber

Forsooth! Fivesooth, even!

Extra points if you read that in Snagglepuss’s voice. Or even know who he is. But I digress.

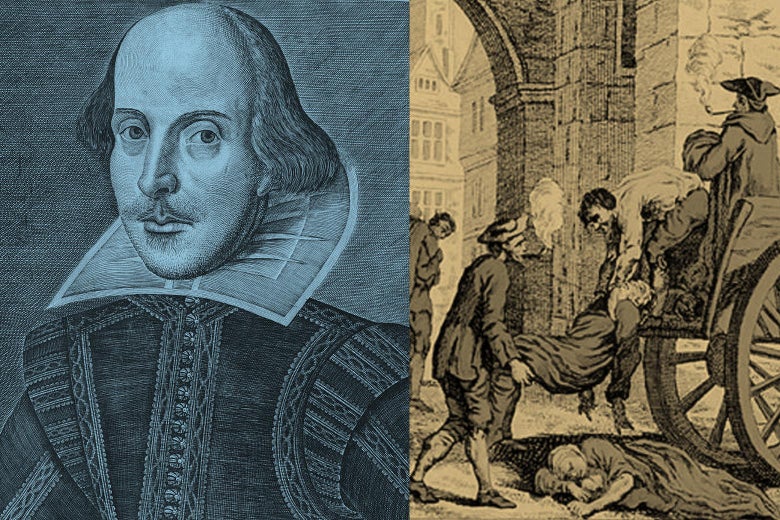

Today is National Talk Like Shakespeare Day! That’s because it’s April 23rd, the anniversary of both his birth and death, in 1564 and 1616, respectively. So I thought it fitting that I share my own personal Shakespearean tale.

I was stationed in South Korea with a squadron providing Close Air Support near the DMZ. The commander discovered that I was reasonably proficient in grammar and spelling, and I was eventually rewarded (?) by being allowed (?) to review every…single…dadburned performance report, decoration submission, and award package for the entire squadron. So be cautious about doing things well, because they may become your full-time job.

But back to the story. The commander was pleased enough with my word wrassling that he wrote in my performance report, in a wild burst of blazing hyperbole, that I “could teach Shakespeare to write.” It was nice of him to say so. And then the sentiment was made even more immortal in the going-away shadow box I was given when I finally finished my tour and headed back to the States.

I’ve happily displayed the shadow box on my office wall since then, not only as a reminder that I survived what the assignments folks at Randolph AFB called the “worst assignment in the Air Force for a Chief,” but also because it’s a delightful case of Shakespearean literary irony. I get a chuckle every time I see it.

Do you see it?

By trying, we can easily endure adversity. Another man’s, I mean.

— Mark Twain

Here we are, all quarantined up and biding our time until the current pestilence is under control. Some of us have extra time on our hands, and hopefully we’re using it wisely. If you’re a writer, it would be a perfect time to write. And that might be one of the things you didn’t know about William Shakespeare and how his writing was inextricably linked to the plague, in so many ways.

He wrote when his troupe couldn’t perform because of the plague. The plague is what turned Romeo and Juliet into a tragedy. The plague thinned out his competition and enabled his collaborations. Yup, there were a whole lot of really, really bad things about the plague, but ol’ Will managed to make it work for him.

Here, from Slate.com, is a fascinating piece about all that, by Ben Cohen, adapted from his new book, The Hot Hand: The Mystery and Science of Streaks. And it might just give you a tip or two about turning adversity into advantage.

One summer day in 1564, a weaver’s apprentice died in a small village in the English countryside, a local tragedy that was immortalized in the margins of the town’s records. Next to the name of the weaver’s apprentice were three ominous words: “Hic incipit pestis.”

Here begins the plague.

The plague wiped out a sizable portion of this particular town. Who lived and who died was seemingly a matter of chance. The plague could decimate one family and spare the family next door. In one house on a road called Henley Street, for example, was a young couple who had already lost two children to previous waves of the plague, and their newborn son was 3 months old when they locked their doors and sealed their windows to keep the plague from invading their home again. They knew from their unfortunate experience that infants were especially vulnerable to this morbid disease. They understood better than perhaps anyone on Henley Street that it would be a miracle if he survived. It was as if every family was flipping a coin unfairly weighted toward heads and betting a child’s life on tails. But when the plague was done with this small village in the English countryside, a little town called Stratford-upon-Avon, the couple breathed a sigh of relief that their young boy was still alive. His name was William Shakespeare.

There’s a possibility that Shakespeare developed immunity to the plague because of his exposure when he was an infant, but that speculation began only centuries later and only because the plague was a constant nuisance to Shakespeare. “Plague was the single most powerful force shaping his life and those of his contemporaries,” wrote Jonathan Bate, one of his many biographers. The plague was naturally a taboo subject for much of Shakespeare’s writing career. Even when it was the only thing on anybody’s mind, nobody could bring himself to speak about it. Londoners went to the city’s playhouses so they could temporarily escape their dread of the plague. A play about the plague had the appeal of watching a movie about a plane crash while 35,000 feet in the air.

But the plague was also Shakespeare’s secret weapon. He didn’t ignore it. He took advantage of it.

One example of this curious phenomenon is Romeo and Juliet. It’s basically impossible to appreciate the truly bonkers nature of this play when you read it for the first time. So let’s do it now. You probably remember the basics of the plot: Romeo and Juliet are born into rival families; Romeo and Juliet fall in love; Romeo and Juliet die. But do you remember how any of that happens? Maybe not. And did you know the plague is what ultimately drives Romeo and Juliet apart? I bet you didn’t. Maybe you vaguely recall the only explicit mention of plague in the entire play: “A plague o’ both your houses!” Mercutio says on his deathbed. But the plague is actually everywhere in Romeo and Juliet.

Spring is when you feel like whistling even with a shoe filled with slush.

— Doug Larson

Never take life for granted. Savor every sunrise, because no one is promised tomorrow…or even the rest of today.

— Eleanor Brownn